Writing by Hildegard Westerkamp

Are you using a portable device? Please switch to landscape mode!

Soundwalk Practice: An Agent for Change?

By Hildegard Westerkamp

Published in the Proceedings of The Global Composition 2012, Conference on Sound, Media, and the Envrionment

Media Campus Dieburg, Hochschule Darmstadt, Germany, July 25 – 28, 2012

ABSTRACT

From the origins of soundwalking in the 1970’s to the increased interest in soundwalks nowadays, this presentation will examine the multitude of approaches that have been developed towards this practice of environmental listening. It will also address questions that naturally emerge from this practice, such as: does the current upsurge in soundwalking activities indicate a specific social, cultural, environmental or possibly even spiritual need? What do participants experience, explore and learn on soundwalks? What is the teaching and why is it important? How can it be developed further, in fact, so much so that it becomes an accepted, integral part in the design, change or improvement of any environment? It is anticipated that answers may emerge from the questioning itself, from the ongoing listening and most importantly, from the DOING of soundwalks.

PROLOGUE

How can I draw you into your listening while you are reading this presentation? How do you find access to your own listening at this moment? How do I stay connected to mine while writing? Communication, connectedness and understanding happens when we are continuously in touch with our listening.

In our work as acoustic ecologists, the object is always to encourage listening and to create situations or frameworks in which it feels safe to open our ears to the sounds, languages and musics of the world. Ideally we do this no matter whether we conduct a soundwalk, write a text, give a workshop or presentation, design a soundscape, create a sound piece or concert, or simply move through daily life.

Balance in acoustic ecology cannot merely be a theoretical construct. It must also be a felt knowledge, a sensed experience of how to balance listening and soundmaking as a person, community, or culture. Writing about such a balance – as is happening right now – ideally means that the sounding words are in balance with the author’s listening.

It is precisely in the search for and maintenance of such a balance between soundmaking and listening that soundwalks play an important role. They remind us of our listening capacities, of everything we miss when we forget to listen and of our role as soundmakers in the soundscape. They teach us to trust our perception as a source of vital information and as a reliable ground from which to build thoughts, ideas and actions towards a healthy sound environment. They are a listening practice, which reveals the sounding place to the listener and opens inner space for noticing. It is precisely this - the noticing - that creates a sense of inspiration, excitement and potentially new energy and resolve for active change.

CONTEMPLATING A SOUNDWALK OF THE 1970S

Soundwalks were initiated by R. Murray Schafer and appealed to me greatly from the start. The immediate and repeatedly occurring impact on listening that soundwalks have on anyone willing to surrender to the experience is not dissimilar to the first noticeable ear opening I felt after hearing a lecture by Schafer in the early 70s. Potentially every soundwalk has this same effect – an AHA moment not to be forgotten, powerful enough to stop us in our tracks, and redirect the course of our day, possibly even of our entire life. Soundwalking as a regular practice then re-invigorates our memory of that moment and our resulting resolve to stay aurally connected to the environment both in our listening and soundmaking.

When you take your ears for a soundwalk, you are both audience and performer in a concert of sound that occurs continually around you. By walking you are able to enter into a conversation with the landscape. Begin by listening to your feet. When you can hear your footsteps you are still in a human environment, but when you become separated from their sound by the ambient noise, you will know that the soundscape has been invaded and occupied.1

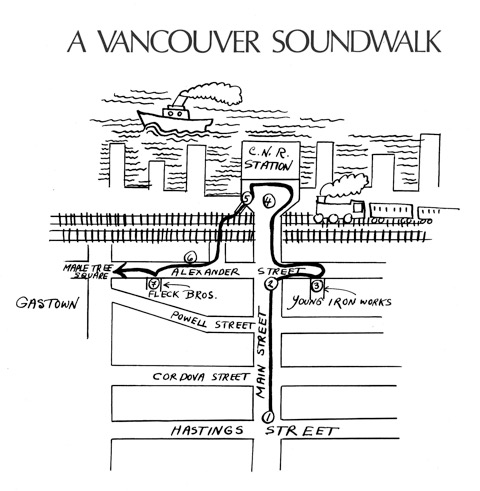

This was the language used by us, the members of the World Soundscape Project (WSP) in 1973, in a soundwalk published in The Vancouver Soundscape, a document of 2 LPs and a book. A map (see Appendix) outlined a walking route with numbered listening stops and a series of questions and statements about the sounds one may encounter. The idea was that readers of the document would be moved to get out there and walk the route in their own time and follow the listening suggestions.

Take a Hastings or Victoria bus in downtown Vancouver as far as Main Street. As you deposit your fare, notice the different sounds made by the various coins. Ask the driver to call out Main Street. If you are fortunate, you will encounter a truly professional driver who has his street-calling technique developed to a bardic form. En route, close your eyes and listen to the environment around you. How many languages are being spoken? What sound patterns occur at each stop?1

Your listening most likely has turned inward while reading these words, comparing them to your own sound experiences on buses in your hometown, your city. What are the sounds of bus fare payment there, now in 2012? Do you hear any coins anymore? Who is calling out the bus stop names and what is the quality of that voice? What languages are spoken in your busses? And today we would want to point the soundwalker to new sounds such as music spilling out of iPod headphones, cell phone ringing or people making calls.

The space between hearing the above quote and your own inner thoughts is a place of significance, where movement occurs fluidly between our outer and inner listening. There we have the opportunity to notice and contemplate the significance of the changes in the soundscape, as in the example above. It is this ever-changing character of the soundscape as well as the fluidity of our listening which creates both the fascination and the deep challenges in our work as acoustic ecologists.

1) Disembark at Main Street and walk north towards the waterfront. Note how the traffic noise changes on the way and at what point you are re-united with the sound of your footsteps.

2) At the corner of Main and Alexander, stop and listen to the hum of the Western Electric neon light. Can you find its predominant pitch by humming it.1

By suggesting to listen to very specific sounds the ears are opened to all sounds in the environment. Listening to footsteps is a simple way of contemplating the relationship between our own sounds and those of the world around us – a relationship that is also in constant flux. It is a way of becoming conscious not only of our own role as soundmakers, but also of the many sound interactions around us.

The suggestion to hum along with an electrical hum, exploring its fundamental pitch and harmonics, not only creates awareness of an all-pervasive ambient sound that is usually ignored and therefore allowed to spread in an unencumbered way, but it is also an opportunity to use one’s voice – a significant issue especially in societies where people who sing and vocalize spontaneously have become an ‘endangered species’, their live vocal expressions masked or even discouraged by the many recorded music environments. But the person, who does hum along, will never be unaware of electrical drones again! Further interest in this sound may expand into a global consciousness about the different electrical cycles in the world: 60 cycles (in the pitch of B) and 50 cycles (in the pitch of G#), which are global keynote sounds in our electrical age, as documented on the “Hum Map of the World” created by the World Soundscape Project. 2

The Vancouver Soundwalk continues towards the harbour and across railway tracks, but today can no longer be followed exactly, as street patterns have changed, buildings have disappeared, new ones have been built and the harbour has been modernized. All the more interesting it is to walk there now and compare today’s soundscapes with those suggested in 1973. The walk ends in the oldest part of Vancouver, Gastown, now mostly a tourist attraction.

Strains from itinerant street musicians will join the collage of young voices at play, old voices in reminiscence, and the new voices of commerce, but it will be your choice as to how to interpret them. Every time you repeat the walk, new impressions and variants of old ones are inevitable – you need only to listen for them! 1

All the above examples were designed for readers, in an attempt to transfer the lived, embodied experience of going on a soundwalk to a listening experience while reading. For further such examples see the Appendix.3 But a vital question remains: is the text strong enough to go beyond that experience closer to the actual practice of soundwalking, to studying the soundscape, closer to action and to making changes? What is the balance and continuity between our listening practice and our follow-up actions in our private and professional lives?

SOUNDWALK ACTION

There is not much new to say about soundwalks and yet going on a soundwalk – doing it – contains new listening experiences and perceptual surprises every time. This is the nature of a soundwalk, its very essence: the new in soundwalks is revealed and deepened through repeated soundwalking practice. In fact it is in the regular practice of soundscape listening where felt and sensed knowledge about the sonic environment and its ecology is located – a knowledge still widely undervalued.

When the World Soundscape Project was organizing an all-day Noise Workshop at Simon Fraser University in 1973 for officials from all municipalities in the Greater Vancouver Regional District I was given the task to create a number of soundwalks. Modeled on the above Vancouver Soundwalk I explored various routes on campus, made maps and wrote listening suggestions and questions for workshop participants. (See last map in Appedix). I remember feeling both excited by the task and slightly awkward, as I sensed that this part of the workshop was perceived at best as a pleasant entertainment by most participating officials, at worst as mere kids play, bordering on the silly. The fact that I was quite young at the time and one of very few females did not help.

But something important was at stake: civic noise bylaws in the Greater Vancouver Regional District were outdated and there was a general consensus that they needed to be improved and adapted to modern urban society. We offered the workshop in the belief that we could influence the quality of the proposed noise bylaws: we knew that it was not enough to fight worst noise offenders with these laws, but much more importantly it seemed essential that Vancouverites would be educated about the soundscape as a whole and about their role and responsibility as soundmakers and listeners. What better way than to inspire those creating the new noise bylaws to listen to the sound environments they were going to regulate? It was this prospect of potentially influencing the consciousness of lawmakers and thus hopefully the quality of the new noise legislation that strengthened my belief in the power of direct listening action. Soundwalks in such a context, I believed then and believe now, have the potential to initiate significant change.

Imagine beyond this, school children creating soundwalks in their own schools - soundscapes in dire need of change. Imagine those children also recording the school soundscape so that the listening can be shared with others, can even be broadcast on radio or the web?4 The quality of soundscapes in educational environments and institutions can then be elevated into a major issue in need of attention.

Imagine further soundwalks specifically designed for town planners to listen to neighbourhood soundscapes; for architects to consider the acoustic conditions for communication in all manner of buildings; for acoustical engineers to listen to and reduce the proliferation of air conditioning sounds and machinery noise; for law makers to implement improved sound transmission and absorption regulations in the building code; for hospital administrators, doctors and staff to improve hospital soundscapes; for media people to encourage responsible use of media sounds in public places; for developers and contractors to include sound consciousness into their project planning process; and for so many more....

“It is about the capacity to engage”, a colleague and friend said the other day when we were talking about the importance of soundwalks. The multitude of distractions through cell phones, iPads and internet seem to endanger people’s ability to engage in this type of environmental listening. Soundmaps in the internet cannot be a replacement for soundwalks. A click on a 1-minute sound recording while sitting alone in front of the computer screen, often listening on mediocre speakers or earbuds, does not offer the depth of listening that a 1- hour group soundwalk offers. It may connect us globally for a moment to another place and that can be exciting of course. But as Canadian author Jonathan Sterne says, “the distracted listener was written into this technology.”5 And the Canadian journalist and science fiction author, Cory Doctorow defined the internet ironically as “an ecosystem of interruption technologies.”6

Exciting and informative as the internet can be, our capacity to engage with place and our daily surroundings is severely challenged by our daily involvement with this medium. Again I am addressing the issue of balance here. Soundwalks can reconfigure our global internet flights of fancy by placing us into the Here and Now: feet on the ground, ears perked for the sounding moment. It has been heartening to notice, that younger people in particular – who are prone to spend much time with the various forms of digital social media - are seeking out such a balance intuitively and actively, by participating in soundwalks and by getting intensely involved in planning and leading them. This has been my experience many times in the past years and in different parts of the world where I have conducted soundwalks.

Listening Interlude: Bourges, France, June 12, 1997

It’s 11 p.m. I am walking from the studio near the huge Gothic cathedral and the old town centre to my residence. It’s a 10-minute walk. I pass a bar - its’ music and voices spilling out onto the sidewalk. A car comes and goes. Then silence. Except for my footsteps. A little later I hear a deep rumble from a jet high up in the sky. Then my footsteps are the only sounds again, reverberating in this old stone-built environment.

I am surprised how safe I feel. I know it has to do with the silence. There are only my footsteps. Any additional sound and its location are immediately identifiable. No sound can hide behind another sound. The few cars mask the small nighttime sounds only temporarily. All is laid bare in this silence. But when I pass an apartment building I hear a continuous hum. Careful now, something may be hiding behind this soundwall. A danger may be lurking in the dark.

I realize I have not heard any air conditioning exhausts since I have come to Bourges. Vancouver hums like a factory on clear summer nights like this, with the many high rises churning out their bad air and the traffic never really dieing down. In this town the nightly keynote sound is a deep quiet that seems to keep all other sounds quiet. No one needs to be loud, not even the music and the voices from the bars I passed. Only the mopeds can’t help tearing through the quiet.

SOUNDWALK PRACTICE

Words cannot replace the act of going for a soundwalk. This cannot be repeated often enough. It is in the doing where the real transformation occurs, where the seed for new knowledge and information is located. The task then is to create an atmosphere and framework that attracts people to soundwalks in the first place and then allows participants to descend into a deeper world of listening, where mental blocks and obstructions can be removed, where inner trust to ‘believe their ears’ becomes the ground from which to listen.

The very simplicity of soundwalking contains hidden depths and complexities that reveal themselves in the soundwalk practice itself. The key to change lies in its regularity as it dismantles habitual mental structures and thought patterns, opens the door to inspiration and creativity and allows us to develop an understanding for the natural movement between our outer and inner listening.

Over the years I have become more and more interested in that movement. Why do our own inner thoughts engage our listening more at times than the sounds around us? And why at other times, are we drawn to environmental sounds and do not hear our own thoughts and inner voices? If we understand the relationship and balance between our inner world and outer world listening, then, I believe we also understand more about what our relationship is to our environment.

How often do we think we are listening to the outside world when we suddenly catch ourselves thinking about something completely unrelated. Often we do not notice the moment of switching from outside to inside. In a soundwalk we have the time and opportunity to try to trace this movement more consciously, find out when or why we might turn our attention inside or outside and what might have triggered it. Was it an uncomfortable thought or a loud sound that caused us to switch our listening attention towards the environment? Or was it a certain quality of a sound or the soundscape as a whole that moved us to pay more attention to our inner voices? Or is it subtler than that? Do the shifts occur in a much less obvious fashion?

We cannot answer these questions in one soundwalk. Only repeated practice of this intense inquiry into our own listening movement – listening to our listening – contains information about what kind of listeners we are and how we relate to the world around us. And this knowledge in turn informs our decision-making and our actions in life. Ultimately it is this depth and intensity of listening that we want to transmit when we take people on soundwalks, no matter whether they are city officials, architects, school principals, hospital administrators, parents, real estate agents, teachers, children or our closest friends.

Regular Practice: The Vancouver Soundwalk Collective

In Vancouver we have had the fortunate opportunity to deepen our experience of designing and leading soundwalks because Vancouver New Music under the direction of Giorgio Magnanensi, has scheduled regular walks during its yearly concert seasons since 2003. From the start I perceived them as an exploration of our ear-environment relationship, mostly unmediated by microphones, headphones and recording equipment, an exploration of what the ‘naked ear’ hears and how we relate and react to the experience.

During the first season in 2003 I invited interested people to join me in the planning and designing of future soundwalks. Since then a group of young people has emerged – the Vancouver Soundwalk Collective7 - working together in exploring ever new approaches, new routes and structures, walks with different themes or walks that may contain subtle or clearly ‘planted’ performative aspects.

By now, most members of the Collective have become familiar with the two inherently different aspects of soundwalk listening: that of the participant-follower and that of the leader. As the participant–follower one is allowed the luxury of surrendering to the safety of a guided soundwalk, free of responsibility, free to ignore the rest of the group, free to focus exclusively on ones personal perception. Under such circumstances participants can potentially have an extraordinarily deep listening experience and connect in a new way to the spaces of their city and neighbourhoods.

But once we take the responsibility of creating, composing and leading a soundwalk ourselves invariably our listening, the experience of space, its meanings, our understanding and knowledge of a place, our curiosity, all of that gets deepened even further. Soundwalk leaders must learn to combine attention to their responsibilities with a strong listening presence towards environment, group and their own inner sound worlds. This takes experience and training and ultimately enables them to make decisions on the spot. It is the kind of listening that improvising musicians know intimately well.

As the leader one can attempt to structure a soundwalk like a composition in order to know the larger gestures of the final ‘piece’. One can attempt to find a route that keeps the ears alert, i.e. that offers changes and contrasts, opportunities to rest overburdened ears, etc. But what occurs during the planning of a soundwalk route may not happen at all during the final group walk. Invariably there will be unexpected changes. Crucial then for a well-lead soundwalk that encourages an atmosphere of deep listening and allows participants to feel safe, is the leaders’ ability to stay present in their own listening, no matter what surprises or changes may occur.

A few years ago, I asked members of the collective to articulate how their listening may have shifted since their first participation in a soundwalk. Here are a few samples of their answers:

Stephanie Loveless:

What I remember most pointedly from [the first] soundwalk, was a shift in listening-consciousness. With my vision relaxed, and my feet simply following the group, I began to hear the sounds around me in a new way. They became, first of all, integrated (a complete shifting sound field, rather than a series of individual sounds) and also divorced from their semantic meaning. Somehow, walking in this more unified, more abstract, sound field was (and still is) a trance-like experience. The sounds move through, ‘almost carry ‘ my body, and my attention is awakened and calmed. I am sensitized to the poignant fullness of the everyday.

Pessi Parviainen:

I remember the route snaked through Chinatown. There was a visit to the Supermarket. This I found particularly thrilling - the walk became suddenly a performance. The customers and store staff seemed to notice something out of the ordinary, but only very subtly - they weren't alarmed, but I could tell they sensed something. This was a bit of a revelation to me - that listening isn't really hidden, it manifests in subtle ways.The silent group heightens the act of listening. I don't think that the sounds themselves are heard better; it is the process of listening, the how-it- becomes-heard-in-us, that is heightened. And that to me is a thrill.

I asked further: once you start leading a soundwalk, something else happens. You are not in the safety of being led anymore. Was that an issue?

Chris O-Connor:

That was an issue. The first few soundwalks I led, I did not experience them as soundwalks. I was so much thinking about the pace, thinking thinking thinking, I didn’t listen at all. I had done the work of listening to create the soundwalk, to prepare for it, but when I was in it, I wasn’t listening. But since the last two soundwalks I have [lead], I felt comfortable in doing it, I could listen and shape it as well. I was able to improvise and could really enjoy it, the sounds and the surprises.

Jason Leslie:

The actual leading of the walk was not at all what I expected. If you are being lead you literally let go and open your ears. If you are leading you can’t really let go. You are responsible and there are always things that come up, there are always surprises. There is the possibility that the route you picked would not work out, or may be you are running behind on time, plus there is the responsibility of dealing with a whole group behind you.[On the first walk I lead] I was panicked that the route would be too boring for people and wanted to make sure that there were some points of interest. There is a real pull to thinking that you have to put on a show, but it does not need to be about that. In fact, there is a real immaturity in this attitude.

First-time leaders of a soundwalk often will experience this anxiety that the environment will not sound interesting enough and will not hold the listeners’ attention. Even though a soundwalk may have been prepared in quite a bit of detail, ultimately the leader has little control over what the acoustic environment is going to ‘perform’ during that final scheduled public soundwalk. With more experience in listening and leading one realizes of course that the onus is just as much on the participant-follower: without the focused attention of the listener and a willingness to be open and curious, the soundscape will not be heard, let alone noticed. So, the success of a soundwalk lies in the quality of listening attention of both the leader and the following audience, whether the soundwalk has been pre-planned or spontaneously improvised.

Wende Bartley:

I remember you once said, that the quality of the leader’s listening has a really strong effect on the followers’ ability to listen as well. That in itself is a task of staying focused, like in meditation, honing in your focus, continually coming back to which sound is present right now. It is like a discipline. To hold that listening space is perhaps your strongest responsibility as the leader; to hold that attention and create what some people call a field - a field of listening under which other people can enter in and join you in that listening, It’s a non-verbal form of guidance that you are giving them.8

Grappling with the lived experience of regular soundwalking in a more theoretical context Vincent Andrisani, also a member of the Vancouver Soundwalk Collective, wrote in a recent paper:

As such, the very act of listening can be considered an act of culture; an embodied response that is conditioned and employed in ways that are unique to the socio-cultural and socio-historical position of the listener. And by extension, the attributes, and the communicational significance of acoustic space are also dependent upon the aural history of the perceiver, and the extent to which they have been required to acknowledge and draw upon such information.9

And Ozgun Eylul Iscen, a visiting student from Istanbul and repeated participant in the public soundwalks in Vancouver wrote:

Theorists or researchers from various disciplines emphasize the sensuous interrelationship of body, mind and environment that challenges the understanding of place as static. Rather, [place] is described as an event; as a sphere of contemporaneous plurality, which produces ‘inter-relations’ and which is always under construction. In this sense, its fluidity, constantly changing nature and ‘gathering togetherness’ is pointed out. According to Edward S. Casey, space and time arise from the experience of the place (in relation to senses/living bodies), not vice versa. The place does not exist so much as it ‘occurs’. (Pink, 2009, 28-32)10

At the beginning of this text we read how the World Soundscape Project spoke about soundwalks and listening. The above writings are today’s language used to articulate how soundwalk experiences impact the listener and shift participants’ perception and understanding of the soundscape and their role in it. When I spoke about the ever-changing character of the soundscape earlier and the fluidity of listening I could have said the same about the use of language, as has been documented here. Each context produces its own soundscapes, musics and language expressions. The deeper we listen the more deeply we will understand the significance of this when studying soundscapes, musics and languages of the past and present.

EPILOGUE: DARMSTADT SOUNDWALKS - SOME GUIDELINES

For the last few months I have been in email correspondence with Sam Nyambogam who has been preparing the routes for the three soundwalks offered to all participants of this Global Composition conference in Darmstadt. Below I am reprinting some of the thoughts and suggestions that I sent to him in the process, with the thought that readers may want to use them as guidelines for their own future soundwalk events:

Soundwalk Preparations

Preparations for the soundwalk should be inspiring and fun, if the people scouting out the route let their ears lead them! It is often a discovery of unexpected surprises.

Meeting location: It’s important to find a good location where everyone gathers at the beginning of a soundwalk. Whether indoors or outdoors, it should be a relatively quiet spot, where people can hear a short introduction, ask questions, begin to listen, etc.

End of walk location: It can but does not necessarily have to be the same location as the start point of the walk. It is important, however, to end somewhere where soundwalkers can sit down and where it is quiet enough to have a discussion/exchange among the participants. This will make people feel comfortable and more open.

A post-soundwalk exchange is more important than one might think, as this sort of reflection helps to heighten the significance of a soundwalk experience. Whenever a soundwalk does not include such an exchange, there is a definite sense of non-completion.

Walking together in silence and listening creates a certain connection within the group, which is consolidated when participants hear of each other’s listening experiences, discovering differences and similarities in their perception and their response to sound.

Length of walk: I would allocate 1 hour for the walk, give or take a few minutes, and 30 minutes for a discussion. One hour is a good average time for a soundwalk. It is long enough to get people very much immersed (often there is a marked shift in the listening at the half hour point). And it is short enough to prevent listening fatigue. [For the sake of the conference schedules, these durations had to be shortened]

Preparation of the soundwalk route: The walk should be at a leisurely pace, include stops and acoustically contrasting and/or interesting environments (some typical examples can be: outdoor – indoor; continuous sounds – intermittent sounds; social sounds – mechanical sound; busy street – quiet place; masking noises – dead silence; reverberant space – acoustically dry space; musical sounds – natural sounds; commercial sounds – domestic soundscapes; industrial noise – community soundmarks; etc). It is usually better to plan a shorter route, because it gives flexibility within the time frame to stop for longer periods or to take small detours if a sound invites such a thing. The walking pace can also vary, but participants tend to slow down naturally, even if asked to follow the leaders' pace. This happens precisely because they get intensely involved in the listening process.

For the route planners it is important to remember that even though they may have planned a route full of interest and contrast, the final walk may sound totally different! This knowledge helps to get rid of any expectations of a final 'performance' of the environment. It makes for deeper and more open listening while leading a group. It is a bit like listening while improvising. I am convinced the quality of the leaders' listening influences the group's listening.

To plan a route for an hour's walk usually means one or two scouting sessions of about two to three hours. Then one needs a third session in which the whole route is walked and timed. Sometimes adjustments need to be made in a final check. So, it is more time consuming than one thinks. But it is usually a very inspiring process of discovery.

If there are acoustically particularly interesting places, the soundwalk planners may want to place some sort of soundmaker/musician there to highlight the acoustics. Often it works best when this is done unobtrusively, so that participants cannot be sure whether this person just happens to be there or has been placed there. One can be playful about this.

If by chance a theme suggests itself as a result of all the explorations for the soundwalk, one could give the walk such a focus.

June 19, 2012

After receiving these first suggestions, Sam set out to explore first routes. In the process he and his colleague Gisli made maps, recordings, photos, and videos, which I requested for better understanding of an area I had never visited. It also enabled me to better continue my guidance from the distance in this planning process. In the follow-up emails I posed a few questions to him, such as:

Natural sounds: if we are spending a lot of time in natural environments, can you think of materials (grass, sticks, leaves, anything really) that could be included as soundmaking devices, to be touched and or brought close and moved around soundwalker's ears. ...Try this for yourself and listen to it. It is quite intimate and magical in the same way it can be with sound movement in electroacoustic music.

Texts: we may want to have things happening while we are stopping for longer times, such as reciting relevant texts on listening, perhaps about the place itself, or others.

Conference theme. how about playing back sounds from other cultures in certain spots or situations of the walk, where it would make sense - hidden away, say from a CD in a parked car or someone passing by with a bicycle and some playback system on the back, or coming from a tree or bush. Or a live musician, like a street musician playing music from other places. Or can cell phones be involved in some way: someone walking through the soundwalking group having a loud conversation in one or many languages? What about finding sounds from countries from which some of the participants come? Or doing the opposite, putting a totally incongruous sound, like background music, into a natural environment the way nature films do it - a kind of critical commentary... anything really, related to the 'global composition' theme. I am just thinking out loud here.

Any of these ideas need to be treated with subtlety, not as 'performances', more like fleeting impressions that pass by as if in a dream. And we do not need to do a lot of it.

June 20, 2012

Walking Pace: ...we need to make sure to give enough time for stopping. If it is a large group it takes quite a long time before everyone has arrived. It means that we need to wait for all and then stay longer in that group silence before we start again. It's a time issue....one of the walks could be faster paced on purpose, to learn about listening while we rush through our days - that could be its focus and theme. ...However my sense is that we should never have to rush in order to get back to the starting point.

Trying for more acoustic contrast: I am wondering whether there are any indoor spaces that we can walk through on the routes you are selecting: walking through a store, or a church or a bank, or a lobby or a cafe, whatever. Some places need to be asked if it is okay, or at least forewarned. The change from outdoor to indoor and back creates aural alertness.

Themes: To find focus for the walks, it may help to make them (or some of them) thematic perhaps (as in 'fast-paced walk').

Documentation: Is anyone going to document the walks through video, audio recording and or photos? If so, these people need to be very unobtrusive and subtle about it. Participants should not be distracted by them.

Helpers: You will be with me at the front leading the group - since you will know the routes the best. (I have gotten lost before and we don't have the time for that to happen!!) If there are friends/other students available, it would be good for one or two to walk behind everyone, to make sure that all goes smoothly. Also, if there is a lot of street crossing, going in and out of doors, helpers may be necessary, or at least very useful.

LASTLY...

Every day during this conference you will have the opportunity to walk and open your ears to this place called Dieburg, open them to your own listening, together with the other people in the group. For those of you who have never participated in a soundwalk we wish for you to have an experience never to be forgotten, powerful enough to stop you in your tracks and redirect the course of your day or possibly even of your entire life. For those of you who have been on soundwalks before and may even have developed a regular listening practice, we hope that this walk leads you even closer to studying the soundscape, closer to action, and to making changes in the acoustic environment.

My thanks go to Sam Nyambogam for preparing the three soundwalks, to his colleague Disli who has been assisting in these preparations, and to Sabine Breitsameter for supervising the process on location. See you at the soundwalks!

REFERENCES

1 “A Vancouver Soundwalk” in The Vancouver Soundscape, World Soundscape Project, Document 5, Vancouver 1973, p. 71.

2 Handbook for Acoustic Ecology. Barry Truax, Editor, A.R.C Publications, 1978.

3 “Soundwalking the Wind,” by Hildegard Westerkamp in Soundscape - The Journal of Acoustic Ecology, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 18/19; and “Willow Farm Nursery,” by Hildegard Westerkamp in Soundscape - The Journal of Acoustic Ecology, Vol. 6, No. 2, pp. 34/35.

4 In the late seventies I produced and hosted a radio program on Vancouver Co–operative Radio called Soundwalking, in which I took the listener to different locations in and around the city and explored them acoustically. Given the portability of and much easier access to recording equipment and to the internet, something similar can now be done by anyone and anywhere. See as a recent example: http://www.abc.net.au/local/vi...

5 “The Signal of Noise”, by Teresa Geoff on CBC Radio One, Ideas, June 14, 2012. http://www.cbc.ca/ideas/episod...

6 Quoted in the Guardian Weekly, 23. 9. 2011, p. 31, in “Reading will always be with us”.7 For more information see: http://www.vancouversoundwalk....

8 These interviews were originally conducted for What’s in a Soundwalk? a presentation by the author at the Sonic Acts Conference, Amsterdam, February 2010.

9 Vincent Andrisani, “Aural Ethnography and the Notion of Membership: An Exploration of Listening Culture in Havana”, School of Communication, Simon Fraser University, 2012, unpublished, pp. 4/5.

10 Ozgun Eylul Iscen, “Acoustic Experience of a City with a Sensory Repertoire of Another City: In-Between Soundscapes of Vancouver”, School of Communication, Simon Fraser University, 2012, unpublished, p. 3.

APPENDIX